Growing Greener in Your Rappahannock River Watershed

Case Studies and Talking Points on the Economic and Environmental Benefits of "Green Development" Practices

Funded by:

E.P.A. Sustainable Development Challenge Grant

Chesapeake Bay Restoration Fund

Rivers, Trails and Conservation Assistance Program

Friends of the Rappahannock

Table of Contents

Preface/How to Use this Guide/Acknowledgments iv

Introduction vi

Chapter 1- Bioretention

Attributes and Features 1-1

Case Study: Sommerset 1-6

Case Study: Beltway Plaza Shopping Center 1-9

Chapter 2- Wet Ponds

Attributes and Features 2-1

Case Study: Laurel Lakes 2-5

Case Study: Chancery on the Lake 2-8

Chapter 3- Filtration/Infiltration

Attributes and Features 3-1

Section A- Sand Filters

Attributes and Features 3-A-1

Case Study: Duke St. Square 3-A-5

Section B- Infiltration Chambers

Attributes and Features 3-B-1

Case Study: Capital One 3-B-4

Case Study: Belmont Bay 3-B-7

Chapter 4- Stormwater Wetlands

Attributes and Features 4-1

Case Study: Fredericksburg Christian School 4-5

Chapter 5- Low Impact Ponds

Attributes and Features 5-1

Case Study: VDOT Headquarters- Lottsburg, VA 5-3

Chapter 6- Open Vegetated Channels

Attributes and Features 6-1

Case Study: See Sommerset and Northridge case studies. 1-6 & 9-5

Chapter 7- Streambank Restoration

Attributes and Features 7-1

Case Study: Massaponnax Creek at Lee's Hill 7-4

Case Study: Massaponnax Creek at Southpoint 7-7

Chapter 8- Riparian Buffers

Attributes and Features 8-1

Case Study: Fawn Lake 8-4

Chapter 9- Open Space Development

Attributes and Features 9-1

Case Study: Northridge 9-5

Case Study: Farmcolony 9-9

Case Study: English Meadows 9-13

Chapter 10- Special Golf Course Techniques

Attributes and Features 10-1

Case Study: Belmont Bay 10-3

References R-1

Selected references sorted by topic R-7

Additional internet references and phone contacts R-11

Preface

Can economic growth and good environmental stewardship be compatible goals? Across the region and the country, more and more examples are emerging where developers have benefited economically from "going the extra mile" in designing their projects. We hope that this document will be the centerpiece of effective dialogue that ultimately results in greater use of innovative Best Management Practices (BMPs) throughout the Rappahannock River Watershed.

The real-world case studies of developments in this document are intended to help land developers and site designers become familiar with the practical, hands-on implications of the somewhat nebulous concepts of "sustainable" or "green" development. None of the practices presented herein represent a "silver bullet" that reduces all environmental impacts while also helping or maintaining the developer's bottom line. However, each practice and case study provides a piece of the puzzle, a new angle on the practicality and feasibility of good stewardship in the design of new developments.

How to Use this Guide

This manual is divided into chapters. Each chapter addresses an individual BMP and contains two parts. The first part presents the BMP itself and gives information on design, construction, maintenance, pollution removal, costs and benefits. The second part presents a case study of a development in which this particular BMP was used and the specifics on construction, maintenance, costs and benefits. References are given as parenthetical documentation and listed alphabetically at the end of the entire document.

Please note that all the references listed in this manual can be found in the Friends of the Rappahannock's library and are available for use by local developers, planners, architects, environmental scientists and engineers. We welcome area professionals to come by to discuss their projects and utilize our resources.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the experts in the development, engineering, planning and environmental science fields who contributed to the synthesis of this guidebook. Preparation of the handbook would not have been possible without their generosity and expertise. A special thanks is deserving to the following individuals for their time and guidance. Hal Wiggins of the USACE for his information on Fawn Lake and the Massaponnax Creek restoration projects, David Tice of David Tice & Assoc. for his help with the Lee's Hill case study, Bob Pickett of VDOT for his help with the Lottsburg project, R.J. Keller of R.C. Fields, Inc. for his information on the sand filters at Duke Street Square, Larry Coffman and Derek Winogradoff of Prince George's Co. DER for their advice on bioretention and the projects at Sommerset and Beltway Plaza, Bob Kaufman of the Michael T. Rose Companies for his information on Northridge and Laurel Lakes, Rick Thomas of J.K. Timmons & Assoc. for his help with the streambank restoration project at Southpoint, Pat Gassaway for the information on Fawn Lake, Bob Sowder of Sentry Realty for his information on the English Meadows case, Don Thurnau for his information on the Farmcolony case study, Jason Vickers-Smith for his help with the Belmont Bay study and Bob Maestro for information on the Belmont Bay and Capital One studies.

Special thanks is also deserving to the following individuals for their assistance with the content and design of our manual: Tom Schueler of the Center for Watershed Protection, Dave Kitterman of the Fredericksburg Area Builders Association, Warren Bell and Larry Gavan of the City of Alexandria, Jim Stafford of Sunrise Builders, Randall Arendt of Natural Lands Trust and Zeke Moore of Sullivan-Donahoe & Ingalls.

Introduction

Developers can choose from a variety of design and engineering alternatives that can turn what once was considered a necessary evil into a useful, enjoyable, and marketable amenity.

- National Association of Home Builders Land Development Magazine (Hilsenwrath and Zachary 1996)

In the past, stormwater management has been considered an unfortunate necessity by environmental regulators and a costly nuisance by developers and engineers. However, recent advances in the field have illustrated that alternative approaches to stormwater control and land development can be implemented which have both environmental and economic benefits.

How development practices can decrease property values

...because infiltration is impeded, the soil's natural filtration action has little opportunity to cleanse the runoff of pollutants...In addition, without adequate percolation, groundwater supplies can become exhausted... (Hilsenwrath and Zachary 1996)

- National Association of Home Builders Land Development Magazine

Land development has several negative impacts on the terrestrial and aquatic environment. These impacts, which are listed below, can have severe implications for property values and homeowner satisfaction. Stormwater BMPs serve the important role of minimizing the environmental impacts of land development, thus helping to protect real estate property values and the natural environment.

- Increase in flooding and associated property damage due to impervious surfaces.

- Larger export of pollutants (i.e. hydrocarbons from parking lots and fertilizers from lawns) which degrades aquatic resources.

- Increased streambank erosion resulting in property loss.

- Altered aquatic and riparian biota and loss of vegetative cover.

- Decreased groundwater recharge rates that lead to failure of wells and low flow levels of streams, lakes and ponds.

How innovative BMPs in development can increase property values

Developers currently can choose from a variety of innovative approaches that will provide quantifiable economic and marketing benefits by enhancing the aesthetics of their development, result in significant cost savings and protect the environment.

Economic and Marketing Benefits

Perhaps the greatest asset of innovative stormwater management is its potential to enhance the aesthetics of a development. Research has shown that people have a strong emotional attachment to water, and that they are willing to pay significant premiums for property fronting well-maintained bodies of water. Stormwater BMPs allow for the possibility of providing a waterbody for aesthetics, recreation and enjoyment while simultaneously meeting all stormwater control requirements. Other practices retain the exisiting vegetation or mimic or improve the natural landscape. Developers nationwide are realizing the potential of stormwater BMPs and are producing innovative structures that benefit their developments both economically and environmentally.

Survey of residents of Columbia, Maryland (Frederick et al. 1995):

- 75% felt that permanent bodies of water increased property values

- 73% said they would pay more for real estate located in a neighborhood with stormwater control structures designed for fish and wildlife use

- 75% prefer urban runoff ponds which contain permanent pools of water, wetlands, and wildlife over the standard dry ponds

- 94% responded that managing runoff basins for fish and wildlife as well as for sediment and flood control would be desirable

- 92% considered wildlife to be extremely important and expressed that their presence outweighed any nuisances they created

Examples of real estate premiums charged for property fronting urban runoff controls

| Location |

Base Costs of Lots/Homes |

Estimated Water Premium |

|

Centrex Homes at Berkley,

Alexandria, Virginia

|

Condominium $330,$368,000 |

Up to $10,000 |

|

Chancery on the Lake,

Fairfax, Virginia

|

Condominium $129,000 - $139,000 |

Up to $7,500 |

|

Townhomes at Lake Barton,

Burke, Virginia

|

Townhome with lot: $130,$160,000 |

Up to $10,000 |

|

Lake of the Woods,

Orange County, Virginia

|

Varies |

Up to $49,000 |

|

Dodson Homes, Layton

Faquier County, Virginia

|

Home with lot: $289,$305,000 |

Up to $10,000 |

|

Ashburn Village,

Loudon County, Virginia

|

Varies |

$7,500 - $10,000 |

|

Waterside Apartments,

Reston, Virginia

|

Apartment Rental |

Up to $10/month |

|

Village Lake Apartments,

Waldorf, Maryland

|

Apartment Rental |

$5 - $10/month depending on apartment floor plan |

|

Marymount at Laurel Lakes Apartments,

Laurel, Maryland

|

Apartment Rental |

$10/month |

| Fairfax County, Virginia |

Commercial Office Space Rental |

Up to $1/square foot |

Environmental Benefits

As development continues at an ever-increasing pace, we are realizing the need to employ practices that are not only economically feasible but that also protect the enviornment. The environmental benefits of the innovative stormwater practices detailed in this document are listed below.

- Reproducing the hydrological conditions in the stream prior to development, which helps prevent flooding and streambank erosion.

- Providing significant pollutant removal thus protecting aquatic resources.

- Preserving or creating wildlife habitat.

- Minimizing erosion thereby reducing sediment in waterways and preserving quality soil on the ground.

- Recharging groundwater supplies providing base flow to streams, wetlands and lakes.

Bioretention

Bioretention is an infiltration or filtering system that uses natural processes to cleanse stormwater. Over the long term, it can be a less expensive BMP option than stormwater ponds, and has additional benefits such as attractive landscaping, "green marketing" and noise and wind breaks.

In fact, bioretention is a much more cost-effective method for treating paved areas than such structural methods as oil-grit separators.

- National Association of Home Builders Land Development Magazine (Hilsenwrath and Zachary 1996)

Introduction

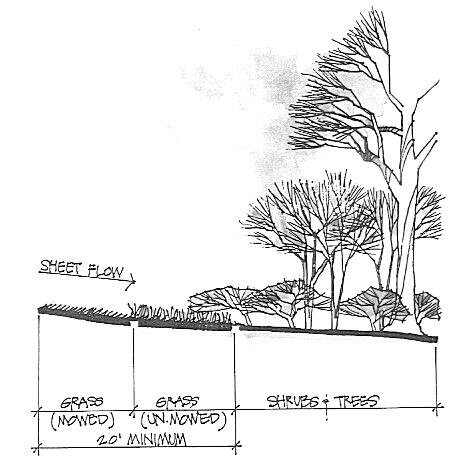

- Designed to mimic pollutant removal mechanisms of plants and soils present in natural forested ecosystems (Claytor and Schueler 1996).

- Runoff is directed as sheet flow to landscaped depressions designed as parking lot islands, parking lot filter strips or "rain gardens" in residential yards (Claytor and Schueler 1996).

- Composed of a grass buffer strip, ponding area, organic or mulch layer, planting soil, sand bed and designated plants (Eng. Tech. Assoc and Biohabitats 1993).

- Vegetation consists of grasses, mulch, shrubs and trees; about 75-80% of normal landscaping plants can be used (Coffman 1997).

- Water is ponded 6 to 9 inches above the organic layer and infiltrates into the soil or evapotranspires over a 48-hour period (Claytor and Schueler 1996).

- Proper design is important and the same person should be with the project from planning through construction (Pasquel 1999).

Schematic of bioretention filter (Claytor and Schueler 1996)

Applications and Restrictions (Eng. Tech. Assoc. and Biohabitats 1993)

- Suitable for commercial, residential, and industrial developments.

- Slopes must be less than 20%.

- Suitable for all soil types if an underdrain is used. For applications without an underdrain, sandy or sandy-loam soils are required.

- Stabilized areas should be maintained to minimize sediment loading and subsequent clogging.

- Water table must be at least 6 feet below ground surface.

Active Pollutant Removal Processes

Bioretention provides increased surface area and extended contact time of pollutant with soil and plant material. These two factors allow for enhanced pollutant removal via filtration, infiltration, microbial reactions, plant uptake and adsorption.

Estimated Pollutant Removal of Bioretention

| |

Water Quality Parameter |

Removal Rate (%)

|

| |

Total Suspended Solids |

93

|

| |

Total Phosphorus |

65

|

| |

Total Nitrogen |

49

|

| |

Metals |

95

|

(Schueler and Claytor 1999; Davis et al. 1998)

This bioretention facility in suburban Maryland provides a highly

attractive landscaped entrance to a business

Economic and Marketing Benefits

- Allows for "green marketing."

- Consumes relatively little land (about 2,000 sq. ft. per impervious acre) (Eng. Tech. Assoc. and Biohabitats 1993).

Construction (Brown and Schueler 1997a)

- The most reliable predictor of bioretention cost is water quality volume, which is the volume of stormwater that is required by ordinance to be treated.

- Total costs for a bioretention area is estimated using the following equation:

TC = (6.88)(WQV0.991) r2=0.96

where: TC = total cost in 1997 U.S. dollars

WQV = water quality volume

- Bioretention generally costs $6.40 per cubic foot of stormwater treated.

Maintenance (Eng. Tech. Assoc. and Biohabitats 1993)

- Inspect trees and shrubs twice per year and replace any dead or damaged vegetation.

- Replace mulch, prune and weed as needed to maintain aesthetic qualities of the BMP.

- Add an alkaline substance (e.g. limestone) one to two times per year to prevent acidification of soil.

- Maintenance costs for a bioretention site are comparable to costs for maintaining the standard required landscaping.

Environmental Benefits

- Recharges groundwater supplies providing baseflow to streams and wetlands.

- Mimics predevelopment conditions and maintains the predevelopment hydrograph for all design storms by infiltrating stormwater into the soil and groundwater table rather than detaining it for future release.

- Enhances pollutant removal.

Additional Benefits

- Improves the aesthetic qualities of the landscape.

- Serves as wind breaks and urban noise buffers.

- Provides shade thereby reducing parking lot temperatures.

- Provides wildlife habitat.

Contacts and References

- Larry Coffman. Department of Environmental Resources. Prince George's County, MD. .

- Claytor, R.A. and T.R. Schueler. 1996. Design of Stormwater Filtering Systems. A report prepared for Chesapeake Research Consortium, Inc. December. Ellicott City, MD: Center for Watershed Protection.

- Engineering Technologies Associates, Inc. and Biohabitats, Inc. 1993. Design Manual for the Use of Bioretention in Stormwater Management. A report prepared for Prince George's County Watershed Protection Branch. June. Landover, MD: Prince George's County Department of Environmental Resources.

Bioretention

Sommerset

In this typical suburban development, shallow landscaped depressions called "rain gardens" were placed on each lot to control stormwater quantity and quality. This resulted in a cost savings of more than $4,000 per lot because the developer did not have to construct a BMP pond and was therefore able to recover 6 lots which would have been lost to space requirements of the pond.

[The 'Rain Gardens' plan at Sommerset is a] more environmentally sensitive-and less expensive-way to develop the site.

- Larry Coffman, Prince George's County Department of Environmental Resources (Daniels 1995)

Introduction to Sommerset

- 80-acre site in Prince George's County, Maryland being developed into 199 homes on 10,000 square foot lots.

- Prices begin at $160,000.

Feature BMP: "Rain Gardens"

- 300 to 400 sq. ft. in size; 1 to 2 rain gardens per lot (Daniels 1995).

- Located at low points on the lots.

- Water is allowed to pool to a depth of 6 inches in the rain garden after each rain event. Complete infiltration of ponded water is achieved within 48 hours (Daniels 1995).

- Combined with grassed swales to replace a curb-and-gutter system.

A typical "Rain Garden" in Sommerset

Economic and Marketing Benefits

- Total cost was approximately $100,000 compared to nearly $400,000 for the BMP ponds originally planned (Daniels 1995).

- Added 6 more lots to the development thus increasing their revenue (Daniels 1995).

- Eliminated the traditional curb-and-gutter system and BMP pond by using the less expensive alternative system of Rain Gardens and grassed swales.

- Marketed the development as environmentally friendly. When told that they were helping preserve the Chesapeake Bay, homeowners and potential buyers became excited and interested in helping (Coffman 1997).

- Perceived by homeowners as free landscaping (Coffman 1997).

Cost Comparison: Closed System vs. Bioretention

|

Description

|

Stormwater Management Pond/Curb & Gutter Design

|

Bioretention System

|

| Engineering Redesign |

0

|

110,000

|

| Land Reclamation (6 lots x 40,000 Net) |

0

|

<240,000>

|

| Total Costs |

2,457,843

|

1,541,461

|

| Total Costs - Land Reclamation + Redesign Costs |

2,457,843

|

1,671,461

|

| Total Cost Savings = $916,382 |

| Cost Savings per Lot = $4,604 |

(Winogradoff 1997)

Construction

- Total cost for each Rain Garden is $500 ($150 for excavation and $350 for plants) (Daniels 1995).

Maintenance

Rain Garden maintenance is as simple as homeowners maintaining their lawn (Coffman 1997).

- Prince George's County Department of Environmental Resources provides a manual of instructions for homeowners on how to maintain Rain Gardens. Included in this manual are what type of plants to use and methods for improving the habitat and aesthetic qualities of a Rain Garden (Curry and Wynkoop 1995).

Rain Gardens can be an attractive and marketable amenity to a site

Comments (Coffman 1997)

Overall acceptance of the Rain Gardens by Sommerset residents has been excellent. Homeowners are actively maintaining the Rain Gardens and have registered very few complaints. Only one of the gardens has had functional problems, which are believed to have been caused by too much water being diverted to it for treatment. There have been no concerns or problems with safety or mosquitoes.

Contacts and References

- Larry Coffman. Department of Environmental Resources. Prince George's County, MD. .

- Curry, W.K. and S.E. Wynkoop, eds. 1995. "How does your Garden Grow?": A Reference Guide to Enhancing Your Rain Garden. Landover, MD: Prince George's County Department of Environmental Resources.

- Daniels, L. 1995. Maryland developer grows "Rain Gardens" to control residential runoff. Nonpoint Source News-Notes 42 (August/September): 5-7.

Bioretention

Beltway Plaza Shopping Center

Vegetated islands in the parking lots were designed to serve as filters for stormwater. These parking lot biofilters were less expensive than traditional stormwater management and also partially fulfilled the landscaping requirements for the development.

[The developers] obviously saved a substantial amount of money.

- Derek Winogradoff, Prince George's County Department of Environmental Resources (1998)

Introduction to Beltway Plaza Shopping Center

- Commercial shopping mall located in Greenbelt, Maryland.

- An existing shopping center was converted into an indoor mall. Additional stormwater management facilities were required as part of the conversion and expansion.

Feature BMP: Parking Lot Biofilters (Winogradoff 1998)

- The parking lot is designed so that all runoff is channeled into these landscaped islands located throughout it.

- Designed to promote rapid infiltration of water, which allows them to handle large volumes of stormwater.

- Stormwater infiltrates through approximately 3 feet of coarse-textured soil and is then collected in perforated pipes and transported to the county's storm drain system.

Parking lot biofilter with inline overflow drain

Economic and Marketing Benefits (Winogradoff 1998)

- Derek Winogradoff of Prince George's County Department of Environmental Resources estimated that the developer saved a substantial amount of money by choosing the biofilters over traditional stormwater management methods, because economic reasons were what drove the developer's decision to use the biofilters.

- Fulfilled the development's stormwater management requirements as well as satisfied a significant portion of its landscape requirements.

- Featured in several slide shows on stormwater management.

Maintenance

- Maintenance costs are approximately the same as that for conventional stormwater management, as reported by the property managers for the development (Winogradoff 1998).

- Maintenance procedures for the facilities are comparable to those for traditional commercial landscaping (e.g. pruning vegetation, weeding and replacing dead plants).

Curb cut inlets and plantings in parking lot biofilter

Contacts and References

- Derek Winogradoff. Department of Environmental Resources. Prince George's County, MD. .

Wet Ponds

Wet Ponds are constructed stormwater ponds that contain permanent pools of water. Their construction costs are comparable to traditional dry ponds, yet they provide many amenities such as recreation, wildlife habitat and increased property values.

Experience has shown wet ponds to be less costly to maintain than dry ponds, more effective in reducing sediment, and more appealing for recreational and aesthetic purposes.

- National Association of Home Builders Land Development Magazine (Hilsenwrath and Zachary 1996)

Introduction

- Also known as retention ponds. Composed of an inlet, a sediment forebay, a permanent pool, an aquatic bench and an outlet structure.

- Must be designed carefully so as to enhance the surrounding landscape and to adequately treat stormwater from its watershed.

- As a general rule, "bigger is better" from an economic and environmental perspective (Schueler 1987).

Schematic of wet pond (Schueler 1987)

Applications and Restrictions (Schueler 1987)

- Most effective in residential or commercial sites greater than 20 acres with a dependable source of water.

- Require significant amounts of land (usually between 2% and 5% of total development size), therefore, they are not suitable for areas where land is at a premium.

Active Pollutant Removal Processes

Effectiveness of pollutant removal is a function of the amount and type of incoming pollutants and the size and design of the permanent pool. The size of the permanent pool in relation to the pond's watershed is the most important factor effecting its pollutant removal. Pollutant removal mechanisms include sedimentation, biological uptake, infiltration and microbial action.

Estimated Pollutant Removal of Wet Ponds in N. Carolina Piedmont

| Pond Characteristic |

Lakeside Pond |

Runaway Bay |

| Drainage area (acres) |

65

|

437

|

| Imperviousness (%) |

46

|

38

|

| Pond area (acres) |

4.9

|

3.3

|

| Mean Depth (ft.) |

7.9

|

3.8

|

| Equivalent watershed storage (in.) |

7.1

|

0.33

|

| Water Quality Parameter |

Removal Rate (%)

|

| Total Suspended Solids |

93

|

62

|

| Total Phosphorus |

45

|

36

|

| Total Kjeldahl Nitrogen |

32

|

21

|

| Pond Area/Watershed Area |

7.5

|

2.3

|

Note the differences in the characteristics of the two ponds and how it affects their ability to cleanse stormwater.

(Schueler 1995b)

Economic and Marketing Benefits

- Increases property values because of aesthetic benefits.

- Offers high community acceptance and landscaping amenities.

Construction (Brown and Schueler 1997a)

- Construction cost for a wet pond of less than 100,000 cubic feet can be estimated using the following equation:

TC = (23.07)(Vs0.705) r2=0.80

where: TC = total cost in 1997 U.S. dollars

Vs = volume of storage of the pond

Maintenance (Schueler 1987)

- Inspect annually to insure proper functioning of the pond system.

- Mow the grassy area surrounding the wet pond (side-slopes, emergency spillway and embankment) at least twice a year to prevent growth of woody vegetation. More frequent mowing may be desirable for recreational and aesthetic purposes.

- Control the weeds, algae and insects if they become a problem.

- Remove debris and litter.

- Complete non-routine maintenance including structural replacement and repairs (every 25-75 years) and removal of accumulated sediment (every 10-20 years).

- Annual maintenance costs for routine and non-routine maintenance generally range between 3% and 5% of the base construction cost.

Environmental Benefits

- Extends the detention times so pollutant removal processes can work.

- Vegetative uptake of pollutants.

- Controls peak discharge.

Additional Benefits

- Creates wildlife habitat.

- Contributes an aesthetic "park-like" setting in which to live and work

- Provides recreation opportunities (e.g. fishing, boating, etc.)

Tips for Maximizing Your Pond Premium (Schueler 1995b)

- Make the pond as large as possible.

- Add items such as a walking trail, picnic tables and a gazebo.

- Properly maintain the pond to prevent unsightly vegetation and nuisances such as algae.

- Construct your pond with safety in mind (e.g. avoid steep slopes, use an aquatic bench).

- Design and landscape your pond so that it enhances the surrounding environment.

Vegetated benches provide water quality/habitat enhancement

and help make this pond an aesthetic amenity

Contacts and References

- Brown, W. and T.R. Schueler. 1997. The Economics of Stormwater BMPs in the Mid-Atlantic Region. A report prepared for the Chesapeake Research Consortium, Inc. Ellicott City, MD: Center for Watershed Protection.

- Frederick, R., R. Goo, M.B. Corrigan, S. Bartlow, and M. Billingsley. Tetra Tech, Inc. 1995. Economic benefits of runoff controls. Nonpoint Source Pollution Control Program. A report prepared for U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Water. <http://www.epa.gov/OWOW/NPS/runoff.html> (21 May 1997).

- Schueler, T.R. 1987. Controlling Urban Runoff: A Practical Manual for Planning and Designing Urban BMPs. A report prepared for Washington Metropolitan Water Resources Planning Board. Washington, DC: Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments.

- Schueler, T.R. 1995. The pond premium. Watershed Protection Techniques 2 (1) (Fall): 303.

Wet Ponds

Laurel Lakes Executive Park

This mixed-use development is centered around two attractive stormwater BMP ponds. Having the ponds as the development's focal point has allowed the developer to introduce a higher priced product into a depressed market, to realize an above average sales pace and to receive a substantial premium on lakefront units.

Having the development situated around the two beautiful lakes has allowed us to do three things: (1) "to introduce a higher priced product which made us more money", (2) "to move product when everyone else was having trouble selling" and (3) "to take a difficult site and make it work.

- Bob Kaufman, Developer, Michael T. Rose Development Co., Inc. (1997)

Introduction to Laurel Lakes

- Mixed commercial and residential property in Laurel, Maryland.

- Parts of the development are centered around two large wet ponds.

- Lakefront property includes townhouses, ranging from $115,000 to $150,000, and first-class office space.

Feature BMP: Wet Pond

- Lake in the commercial section is surrounded by walking and jogging trails, picnic tables, restaurants and a nice lawn. People like to be in that office park because of the lake (Kaufman 1997b).

View of the lake taken from the front door of an office condominium

Economic and Marketing Benefits

This is one of the most successful developments we've ever done (Kaufman 1997b).

- Depending on layout and size, office space fronting the lake rents for a premium of $100 to $200 per month, relative to non-lakefront units (Frederick et al. 1995).

- On average, first-class waterfront office space in Prince George's County, Maryland rents for a premium of between $1.00 and $3.50 per square foot (Frederick et al. 1995).

- Offers a unique environment in an otherwise ordinary area that makes the development easier to market (Kaufman 1997a).

- Allowed the developer to maximize the land by putting in "back-to-back" townhouses and office condos. The units fronting the lake did not have front door parking and normally would have sold for a reduced price, however, because they front the lake, they received the same price.

View of the second lake with adjacent townhouses

Note near-water vegetation that provides runoff filtering and cover for fish

Construction

- Constructed by damming an existing creek.

- Now used as the development's stormwater BMPs.

Maintenance

- The lakes and surrounding facilities (e.g. clubhouse, walking trails) were donated to the City of Laurel who is now responsible for their maintenance (Kaufman 1997a).

Contacts and References

- Bob Kaufman. National Vice President, Michael T. Rose Development Co., Inc. Laurel, MD. .

Wet Ponds

Chancery on the Lake

Condominium development centered around a 14-acre wet pond. The lake is marketed as the development's feature and this strategy has resulted in an increased sales pace relative to that of competitors. Furthermore, a premium of $7,$10,000 is realized on lakefront units.

[The lake] has definitely increased our sales pace over that of our competitors. Every month we get some of our competitors sales, and I'm certain that it's primarily due to the lake.

- Debora Flora, Sales Manager, Chancery Associates (1997)

Introduction to Chancery on the Lake

- 7-acre, unit condominium development in Alexandria, Virginia centered around a large urban runoff pond.

- Prices for the condominiums range from $129,990 to $139,990 (Frederick et al. 1995).

Feature BMP: Wet Pond

- 14-acre pond surrounded by picnic tables, a gazebo and a walking trail. A fishing pier will also be built (Frederick et al. 1995).

Economic and Marketing Benefits

- $7,000 to $10,000 premium for condos that front the lake (Flora 1997).

- Above average sales pace for the area and the condominium market. A significant number of their sales come from buyers who have shopped around and have settled on Chancery because of the attractive lake (Flora 1997).

- Marketed as the feature selling point of the development (Flora 1997).

View of the rear of the condominiums

Construction (Scanlon 1997)

- Constructed by damming an existing creek. Some excavation of the surrounding area was also performed to achieve the desired shape and volume.

Maintenance

- No maintenance has been required other than mowing of grassed areas, visual inspections of the dam and lake and sediment removal from the rip-rap outfall structure (Scalia 1997).

View of the walkway, picnic area and lake

Additional Benefits

- Serves as a buffer zone between the development and the adjacent 4-lane road.

Contacts and References

- Debora Flora. Sales Manager, Chancery Associates Limited Partnership. Alexandria, VA. .

- Vic Scalia. Halle Enterprises. Silver Spring, MD. .

Filtration/Infiltration

Filtration involves the transfer of water through a porous medium before it is returned by pipe to either a stream or stormwater drain. Infiltration facilities temporarily impound stormwater and discharge it via percolation into the surrounding soil (VADCR 1999). The soil aids in the removal of pollutants from the water before it is released to the groundwater. They are appealing since they help reverse the consequences of urban development by reducing peak flows and recharging ground water supplies.

Introduction

Filtration techniques

Infiltration techniques

Applications and Restrictions (VADCR 1999)

Filtration

- Suitable where the water table is sufficiently lower than the design depth of the facility.

- Attractive for medium to higher density projects because of its high removal efficiency.

- Not recommended where sediment loadings are high and may cause clogging of the filtration device.

Infiltration

- Suitable where the subsoil is permeable enough to provide a reasonable rate of infiltration.

- Should be used to control the water quality volume up to the 2-year design storm. Not effective for large volumes of runoff.

- Underlying topography should not be karst in nature and the water table should be sufficiently lower than the facility to prevent groundwater contamination.

- Adapted for low to medium density development with 38-66% impervious cover.

- Provide no wastewater quantity control. This must be provided by a separate facility.

- Infiltration BMPs should be constructed after stabilization to avoid clogging.

Active Pollutant Removal Processes

Estimated Pollutant Removal of Filtration/Infiltration

| |

|

Filtration

|

Infiltration

|

| |

Water Quality Parameter |

Removal Rate (%)

|

| |

Total Suspended Solids |

81

|

88.5

|

| |

Total Phosphorus |

45

|

65

|

| |

Total Nitrogen |

32

|

82.5

|

| |

Organic Carbon |

57

|

82

|

| |

Lead |

71

|

98

|

| |

Zinc |

69

|

99

|

(Brown and Schueler 1997b)

Contacts and References

- Brown, W. and T.R. Schueler. 1997. National Pollutant Removal Performance Database for Stormwater BMPs. A report prepared for the Chesapeake Research Consortium. Ellicott City, MD: Center for Watershed Protection.

- Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation. 1999. Virginia Stormwater Management Handbook. Richmond, VA: Division of Soil and Water Conservation.

Sand Filters

Sand filters are a type of BMP which use a bed of sand to filter pollutants out of stormwater runoff. The District of Columbia sand filters are placed underground which is an economic benefit, because they utilize zero buildable land and pose no safety hazard to the public. Austin sand filters, or surface sand filters, operate in basically the same way as the underground filters.

Introduction

- Utilize sand as a filtering media to strain pollutants out of stormwater runoff.

- Designed to treat only water quality volume (WQV). Flows in excess of the WQV are diverted away from the filter to a downstream stormwater management facility.

- Four basic design components: (Claytor and Schueler 1996)

- 1. inflow regulator which directs the preferred WQV into the sand filter

- 2. pretreatment structure to extract coarse sediments to prevent clogging of the filter

- 3. filter bed and filter media (usually 18 inches to four feet deep)

- 4. outflow mechanism to return treated water back to conveyance system or which allows the treated water to infiltrate the soil

- This chapter will discuss and profile the underground sand filter, however, the general ideas may be applied to all sand filters.

Schematic of underground sand filter (Claytor and Schueler 1996)

Applications and Restrictions

- Most feasible for development sites less than 5 acres. Not typically cost effective for larger drainage areas (Claytor and Schueler 1996).

- Adapted for sites where space is limited or land is prohibitively expensive for use of traditional BMPs.

- Should be designed to treat runoff from impervious surfaces only (helps prevent clogging).

- Provide no wastewater quantity control. This must be provided by a separate facility.

- Most applicable for industrial and residential sites.

- Provide no aesthetic, wildlife or recreational benefits.

Active Pollutant Removal Processes

The underground sand filter utilizes many components to cleanse stormwater. The wet pool chamber provides the opportunity for sedimentation to occur. The sand filter media provides for filtration, infiltration (if the treated water is not piped out) and adsorption. Microbial reactions will also occur as the sand becomes colonized by microbes.

Estimated Pollutant Removal of a Perimeter Sand Filter in Alexandria, VA

| |

Water Quality Parameter

|

Removal Rate (%) a

|

| |

Total Suspended Solids |

79

|

| |

Petroleum |

ND

|

| |

BOD (5 day) |

78

|

| |

Total Phosphorus |

63 b

|

| |

Total Nitrogen |

47

|

| |

Zinc |

91

|

a. fraction of total incoming pollutant load retained in filter over all storms

b. removal rates were higher if four anaerobic events are excluded

ND parameter not detected in runoff during sampling study

Note: Number of storms = 20

(Claytor and Schueler 1996; Bell, Stokes, Gavan and Nguyen 1996)

Economic and Marketing Benefits

- Use little or no buildable land.

- Pose no threat to the public, therefore fewer liability concerns and costs than with a dry pond.

Construction

- Costs between $25,000 and $30,000 per impervious acre when the concrete shells are cast on site (Bell 1997).

- Concrete shells are now being precast which should decrease costs by at least 20% (Bell 1997).

Maintenance

- Inspect semi-annually to insure proper functioning of the filter. Inspections are also recommended after major storms (Claytor and Schueler 1996).

- Perform corrective maintenance when drawdown times exceed specified lengths (Claytor and Schueler 1996).

- Replace filter cloths every 3-5 years (Bell 1997).

- If regular maintenance is performed, major repairs and maintenance will not be required (Bell 1997).

Environmental Benefits

- Reliably and effectively treat stormwater quality.

- No environmental drawbacks such as groundwater contamination (if designed with underdrains), stream warming or wetland impairment (Claytor and Schueler 1996).

Additional Benefits

- Invisibility of the BMP.

- No potential for mosquito problems.

Contacts and References

- Anacostia Restoration Team. T.R. Schueler, P.A. Kumble, and M.A. Heraty. 1992. A Current Assessment of Urban Best Management Practices. A report prepared for USEPA Office of Wetlands, Oceans, and Watersheds. Washington, DC: Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments.

- Claytor, R.A. and T.R. Schueler. 1996. Design of Stormwater Filtering Systems. report prepared for Chesapeake Research Consortium, Inc. December. Ellicott City, MD: Center for Watershed Protection.

Sand Filters

Duke Street Square

At this ultra-urban site, an effective BMP was required, however, buildable land was very limited. An underground sand filter was installed, which satisfied stormwater regulations, and, because it consumes zero buildable land, the developers were able to add 5 to 7 townhomes which would have been lost to land requirements of a BMP pond.

The sand filter is out of the way, out of sight, and requires very little maintenance, while a dry pond has to be maintained all the time, is an eyesore, and kids like to play in them so they're a safety hazard too.

- Glenn Teets, Project Manager, Wills Land Development Company (1997)

Introduction to Duke St. Square

- 40-unit townhouse development located in Alexandria, VA.

Feature BMP: Underground Dry Vault Sand Filter

- Off-line sand filter system services 1.38 impervious acres.

- Parking lot is designed with grate inlets connected to underground pipes which carry stormwater to the sand filter. Flows in excess of the first 0.5 inches of rainfall are diverted to the city's stormsewer system.

- The filter's concrete chamber was cast in place (Keller 1997).

- Designed with underdrains that transport filtered water to the city stormsewer system (Keller 1997).

View of the inside of a sand filter similar to the one installed at Duke St. Square

Economic and Marketing Benefits

- Uses zero buildable land. Northern Virginia real estate prices of approximately $40 per square foot make it very expensive to install dry ponds, wet ponds or stormwater wetlands (Bell 1997).

- Added 5 to 7 townhouse units which normally would have been lost to the land requirements of a dry pond (Teets 1997).

Construction

- Total construction cost for the sand filters was $41,030. This includes the dry vault sand filter, two monitoring manholes and pipes with connections. The sand filter itself cost $35,197.

- The entire system cost $29,732 per impervious acre, while the sand filter alone cost $25,505 per impervious acre.

Maintenance (Keller 1997)

- Replace filter's sand bed approximately every 5 years.

- Inspect periodically and remove accumulated trash from grate inlets, pretreatment structure and filter bed.

- The home-owners association has set aside a specified annual amount of money for routine and non-routine maintenance.

View of an inlet grate at Duke St. Square

Contacts and References

- Warren Bell. City Engineer, City of Alexandria. Alexandria, VA. .

- R.J. Keller, L.S. Project Manager, R.C. Fields Jr. and Associates, P.C. Alexandria, VA. .

- Glenn Teets. Project Manager, Wills Company. Vienna, VA. .

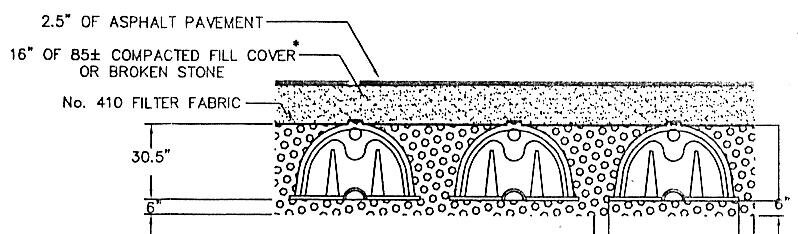

Infiltration Chambers

Infiltration chambers are interlocking, arched chambers that are open at the bottom, allowing the stormwater to infiltrate the subsurface where microorganisms and the soil help remove pollutants and sediment. They use little to no buildable land.

CULTEC chambers effectively serve environmentally sensitive areas while making valuable land available for parking lots, athletic fields and other applications.

- CULTEC Environmental Technologies sales brochure (1999)

Introduction

- Extend the time the water spends in the soil thus allowing for enhanced removal of pollutants.

- Constructed of heavy-duty polyethylene.

Schematic of infiltration chambers (Fisher 1998)

Applications and Restrictions

- Can be placed under most developed surfaces. Available in a heavier gauge for use under trafficked areas.

- Adapted for sites where space is limited or land is prohibitively expensive for use of traditional BMPs.

- Most applicable for industrial, highly urbanized sites.

- Provide no aesthetic, wildlife or recreational benefits.

Active Pollutant Removal Processes

The microorganisms that develop along the soil take in many of the phosphates, nitrates and other pollutants. The soil filters the stormwater and captures much of the sediment and remaining pollutants.

There is no data on the pollutant removal efficiency of the chambers, however it is assumed to be equal to or greater than that of other infiltration practices. Evaluation of the system began in 1999 by the Environmental Technology Evaluation Center using criteria developed by a panel of stormwater and septic wastewater management experts.

Estimated Pollutant Removal of Infiltration

| |

Water Quality Parameter

|

Removal Rate (%)

|

| |

Total Suspended Solids |

88.5

|

| |

Total Phosphorus |

65

|

| |

Total Nitrogen |

82.5

|

| |

Organic Carbon |

82

|

| |

Lead |

98

|

| |

Zinc |

99

|

(Brown and Schueler 1997b)

Economic and Marketing Benefits (CULTEC 1999)

- Polyethylene is cheaper than using concrete pipe.

- Less area and less crushed stone is required with the chambers than with traditional stormwater management systems.

- Much greater lengths of the chambers can be delivered per truckload than of HDPE pipe (1700 ft. compared to 360 ft.)

Construction

- Excavation of the site is required and the fill soil must be sandy to promote infiltration.

- A detailed cost analysis computed $4 per cubic foot including materials, labor, chambers, excavation and fill material (Maestro 1999c).

- The polyethylene chambers interlock so they don't have to be screwed together [which] saves a great deal of labor (Taggart 1999).

Maintenance

- Remove blockages from the intake. Maintenance is minimal.

Environmental Benefits

- Very reliable and effective in the treatment of stormwater quality.

Additional Benefits

- Fifty percent more storage capacity and 1000 times greater drainage potential than conventional piping (CULTEC 1999).

- Contribute to water quantity volume by reducing the peak flow which minimizes scouring in the destination stormwater pond.

- No threat to public safety or potential for mosquito problems.

- Invisible and uses little or no buildable land.

Contacts and References

- Bob Maestro. Environmental consultant, CULTEC Environmental Technologies. .

Infiltration Chambers

Capital One

Case Study Under Construction

Data Gathering in Progress

Additional stormwater management was made necessary on this site due to the additional parking requirements. The site had a preexisting wet pond and did not have the space to expand the pond or use other space-intensive alternatives. Therefore the developer opted for one of the techniques suitable for ultra-urban sites, infiltration chambers.

Introduction to Capital One

- Addition of parking lot required treatment of a greater water quality volume.

- The site is currently served by an unattractive wet pond.

Feature BMP: Infiltration Chambers

- Infiltration chambers serve .65 acres of impervious area.

- The parking lot is designed with a drop inlet at the lowest point to divert the water into the chambers.

- The stormwater is directed into the chambers until the storage capacity is reached. The overflow is then sent to the existing stormdrain emptying into the wet pond.

CULTEC Recharger infiltration chambers (CULTEC 1999)

Economic and Marketing Benefits

- Though more expensive than traditional dry sediment basins, the chambers produce cost savings by conserving space that is then available for other uses. This is especially useful in areas with high real estate prices.

- Poses no threat to the public, therefore fewer liability concerns and costs than with a dry pond.

Construction

- Total construction costs for the infiltration chambers was ?.

- The design unit capacity is 10.4 cubic feet per linear foot. The total capacity of the chambers at this site is 770 cubic feet.

Maintenance

Environmental Benefits

Additional Benefits

Contacts and References

- Bob Maestro. Environmental consultant, CULTEC Environmental Technologies. Occoquan, VA. .

- Doug Tait. General contractor, W.C. Spratt. Fredericksburg, VA. .

- Kim Fisher. Project Manager, McKinney & Co. Ashland, VA. .

Infiltration Chambers

Belmont Bay

Case Study Under Construction

Data Gathering in Progress

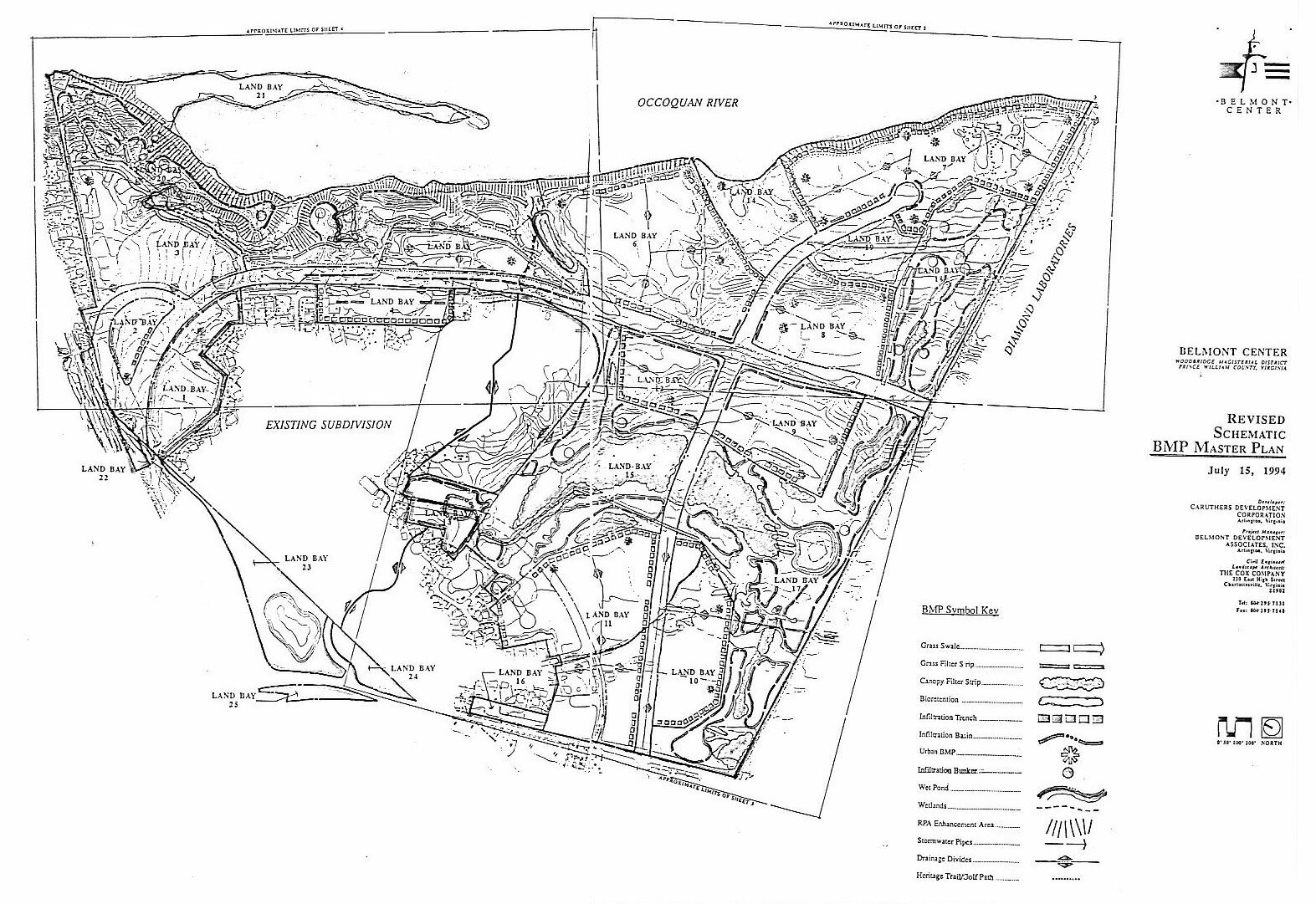

Infiltration chambers are used along Dawson Beach Road to pretreat the stormwater from the adjacent industrial site before it is delivered to the stormwater pond. Dust from the concrete plant causes the runoff water to be too polluted to be discharged directly into the irrigation pond. Chambers will also be used in the planned town center to treat runoff before it enters the Occoquan River.

[The infiltration chambers cost] about $2000, at least 40 to 60% cheaper than using concrete pipe, which would have only moved the water.

- Dennis Shiflett, Woodbridge Institute for Sustainability (Taggart 1998)

Introduction to Belmont Bay

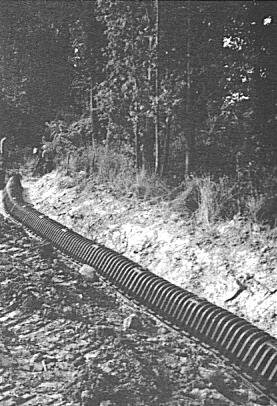

Feature BMP: Infiltration Chambers

- Culvert transporting stormwater from adjacent industries to the golf course BMP wet pond.

Interlocking infiltration chambers used to transport stormwater from adjacent

industrial site to golf course wet pond (Taggart 1998)

Economic and Marketing Benefits

- Cost 40-60% less than concrete pipe (Taggart 1998).

Construction

- Total construction costs for the chamber system was $2000 (Taggart 1998).

Maintenance

Environmental Benefits

Additional Benefits

Contacts and References

- Bob Maestro. Environmental consultant, CULTEC Environmental Technologies. Occoquan, VA. .

Stormwater Wetlands

Stormwater wetlands are constructed wetland systems that use natural processes to control stormwater quantity and quality. Their construction costs are comparable to that for traditional BMP ponds yet they provide many amenities such as wildlife habitat, aesthetic value, recreation and education opportunities. They also have excellent longevity and reliability.

[Stormwater wetlands] provide scenic views and wildlife habitat that enhance the community surrounding the wetlands.

- National Association of Home Builders Land Development Magazine (Hilsenwrath and Zachary 1996)

Introduction

1. shallow marsh

2. pond/wetland system

3. extended detention wetland

4. pocket wetland

Schematic of pond/wetland system (Schueler 1992)

Applications and Restrictions

- Can be adapted to a wide variety of sites.

- Require minimum drainage areas of 25 acres (Schueler 1992).

- Not advisable for heavily industrialized sites or areas subject to inputs of road salts and deicing compounds (Schueler 1992).

- Require more land than most other urban BMPs.

Active Pollutant Removal Processes

Stormwater wetlands are designed to mimic the pollutant removal processes present in natural wetlands. They provide increased surface area and extended contact time for pollutant interaction with soil and plant material. These two factors allow for enhanced pollutant removal via sedimentation, filtration, infiltration, microbial reactions, plant uptake and adsorption.

Estimated Pollutant Removal of Stormwater Wetlands

| |

Water Quality Parameter

|

Removal Rate (%)

|

| |

Total Suspended Solids |

75

|

| |

Total Phosphorus |

65

|

| |

Total Nitrogen |

40

|

| |

Organic Carbon |

15

|

| |

Bacteria |

2 log reduction

|

| |

Lead |

75

|

| |

Zinc |

50

|

Note: The removal rates are for the pond/wetland system.

(Schueler 1992)

Construction (Brown and Schueler 1997a)

- Total cost of construction for wetland systems is estimated using the same formula as that for wet ponds.

- Construction cost for a wet pond of less than 100,000 cubic feet can be estimated using the following equation:

TC = (23.07)(Vs0.705) r2=0.80

where: TC = total cost in 1997 U.S. dollars

Vs = volume of storage of the pond

Maintenance (Schueler 1992)

- Inspect twice a year for the first three years and on an annual basis thereafter. Analyze items such as species survival, sediment accumulation, hydrology, berms and outfalls during these inspections.

- Clean out sediment forebay every 3 to 5 years.

- Mow surrounding grassed areas on a regular basis to prevent woody growth.

- Maintain to prevent algal growth, noxious odors and mosquito infestation.

Additional Benefits

- Excellent potential for wildlife habitat.

- Expected longevity of 20+ years (Schueler 1992).

- Aesthetically pleasing.

- Less hazardous than the open water of a wet pond.

Tips for Enhancing the Pollutant Removal of Stormwater Wetlands (Schueler 1992)

- Increase the volume of runoff to be treated (Schueler 1992).

- Increase the surface area to volume ratio (Schueler 1992).

- Use a sediment forebay for pre-treatment and to distribute the flow throughout the wetland (Schueler 1992).

- Increase the effective distance from inlet to outlet by creating a meandering flowpath (Schueler 1992).

- Install a submerged gravel filter at the outlet to help foster denitrification (Claytor and Schueler 1996).

Contacts and References

- Anacostia Restoration Team. T.R. Schueler, P.A. Kumble, and M.A. Heraty. 1992. A Current Assessment of Urban Best Management Practices. A report prepared for USEPA Office of Wetlands, Oceans, and Watersheds. Washington, DC: Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments.

- Schueler, T.R. 1992. Design of Stormwater Wetland Systems: Guidelines for Creating Diverse and Effective Stormwater Wetland Systems in the Mid-Atlantic Region. A report prepared for Nonpoint Source Subcommittee of the Regional Water Committee. October. Washington, DC: Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments.

Stormwater Wetlands

Fredericksburg Christian School

A two stage pond/created wetland system used to cleanse runoff and serve as an outdoor classroom and community demonstration project.

Introduction to Fredericksburg Christian School (Foss 1997)

- Private school servicing students from pre-kindergarten through 12th grade.

- Four campuses located in the Fredericksburg area. The newest campus is a high school facility being constructed on 20 acres of a 75-acre site in Spotsylvania County.

Feature BMP: Two Stage Stormwater Pond/Wetland System (Tippett 1997)

- First stage: wet pond designed to hold runoff from the site and function in primary treatment. This pond will provide extended detention for settling so as not to overload the wetland with sediment.

- Second stage: wetland system constructed to retain and infiltrate overflow from the pond. The natural processes in the wetland system will provide very high pollutant removal rates.

Conceptual design of FCS Stormwater Wetland/Pond

Economic and Marketing Benefits (Foss 1997)

- Serves as an outdoor classroom for the Fredericksburg Christian School students and the community.

- Provides a demonstration stormwater BMP project for the development community, which will enhance the school's reputation in the area.

- Helped the local Soil and Water Conservation District and citizen groups secure grant funding to cover design and building costs because of the innovative nature of project.

- Media coverage of the project helped with school marketing.

Construction (Tippett 1997)

- Low impact berms were used in an existing forested area to create the impoundment for the wetland system.

- Estimated cost was $2,000 for earth moving and rip-rap.

Maintenance

- Remove sediment from the pond (every 25-50 years).

Environmental Benefits (Tippett 1997)

- Provides extremely high levels of pollutant removal by two-stage treatment.

Additional Benefits

- Use pond area as an irrigation source (Tippett 1997).

Contacts and References

- Dr. Gary Foss. Superindentent, Fredericksburg Christian School. Fredericksburg, VA. .

- John Tippett. Executive Director, Friends of the Rappahannock. Fredericksburg, VA. .

Low Impact Ponds

Low impact ponds present an alternative method of constructing a BMP pond. With this method, the natural terrain and vegetation is left intact, and a natural ravine is dammed to form a dry detention pond. This results in significant cost savings because no land has to be cleared and excavated. Furthermore, a normally unsightly BMP pond is hidden from view.

Introduction

- Similar to a standard dry pond except that the land is not cleared, and an alternative dam structure is used to replace an earthen berm.

- Native vegetation is left in place and utilized in the pollutant removal process.

- Natural topography is used as the banks of the pond.

Applications and Restrictions

- Applicable to all types and sizes of developments.

- Must have suitable topography to allow for "low-impact" construction.

- Forested environments are the most suitable, because they allow for maximum concealment of the BMP pond.

- Damming of streams is a regulated activity. Streams capable of supporting migratory fish populations are not appropriate for this BMP.

Active Pollutant Removal Processes

Low impact dry ponds use natural ecosystems to control stormwater quantity and quality. They provide increased surface area and extended contact time for pollutant interaction with soil and plant material. These two factors allow for enhanced pollutant removal via sedimentation, infiltration, microbial reactions, plant uptake and adsorption. The estimated pollutant removal of low impact ponds is assumed to be similar to that for standard extended detention dry ponds.

Economic and Marketing Benefits

- Minimal amount of clearing, grading and excavating.

- Reduced maintenance costs since it does not require mowing.

- Decreased liability concerns (Pickett 1997a).

- Same facility provides for short-term erosion and sediment control as well as long-term stormwater management. This reduces the need for silt fences, hay bales, etc. (Pickett 1997a).

- Reduced risk of failure. The timber dam is much more stable than earthen berms which are subject to wash-outs (Pickett 1997a).

Construction

- Costs will vary widely between projects depending on topography, type of dam used, etc.

- Construction costs will generally be much less than for conventional dry ponds.

Maintenance (Harper 1997)

- Removal of accumulated sediment from the sediment forebay (every 5-10 years).

- Semi-annual inspection and replacement of dam structure when required (estimated longevity of 25-30 years for treated timber dam) (Pickett 1997a).

- Periodic inspection to insure proper performance.

Environmental Benefits

- Very little land disturbance during the construction and installation of the BMP.

- Recharge of groundwater supplies.

- Use of mature, native vegetation in the pollutant removal process.

Additional Benefits

- Unattractive BMP hidden from view.

- Pond and timber structure is ready for operation as soon as installation is complete.

Low Impact Ponds

VDOT Facility- Lottsburg, VA

An innovative dry pond was installed at this site to account for its unique surroundings. A natural ravine was dammed with a timber structure to form the basin of the dry pond. This resulted in a considerable cost savings (at least $23,500), plus a normally unsightly and hazardous BMP pond was hidden from view.

The main benefit was from a construction management standpoint. We had to disturb very little land to construct [the BMP], and it was a fail-safe safety valve for our erosion and sediment control. Plus, all the other little benefits like the cost savings and reduced maintenance add up to make it a great project.

- Bob Pickett, District Environmental Manager, Virginia Department of Transportation (1997a)

Introduction to VDOT Facility

- Area headquarters facility for the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) in Northumberland County, Virginia.The BMP was installed to account for facility expansion.

Feature BMP: Low Impact Dry Pond

- The site was left in its natural state and a timber structure was used to dam the dry pond instead of the standard earthen berm. The timber dam is 70 feet long, 8 feet tall and extends 3 feet into the bank on each side. The pond services 10.1 acres of improved surfaces.

- Utilized the natural terrain as the banks of the dry pond to prevent the mass clearing and excavation normally associated with a BMP pond.

- A small rip-rap structure was installed to act as a dam for the sediment forebay, which is the only visible part of the pond. This was installed at the head of the pond in a cleared area so that it would be accessible for clean outs.

Construction

- Total construction costs (materials and labor) for the project were $11,453 (Pickett 1997b).

- Realized a cost savings of at least $23,500, since the projected costs for installing a standard dry pond (with an earthen basin) at this site were $35,000 to $40,000 (Harper 1997).

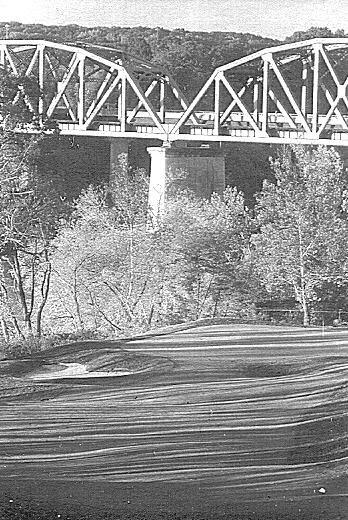

View of the pond basin, riser and timber dam

Environmental Benefits

- BMP was built first and was in place before VDOT began construction (Pickett 1997a), thereby controlling construction erosion and sedimentation.

View of the pond basin and riser from atop the dam

The minimal disturbance makes the facility almost

indistinguishable from the surrounding forest

Contacts and References

- Bob Pickett. Environmental Manager, Virginia Department of Transportation. Fredericksburg, VA. .

- Ken Harper, Department of Conservation and Recreation. Richmond, VA. .

Open Vegetated Channels

Vegetated drainage channels replace concrete channels and underground drainage systems. Vegetated systems are much less expensive to install and include many amenities such as enhanced pollutant removal, aesthetic improvements and groundwater recharge.

Introduction

- Vegetated channels used by engineers to convey stormwater runoff that can often be redesigned to promote infiltration and pollutant removal.

- Four types of open channels: drainage channel, grassed channel, dry swale and wet swale.

- Can be designed with underdrains to carry filtered water to a downstream facility or without underdrains to promote infiltration of treated water.

- Coupled with checkdams to provide for control of stormwater quantity and quality.

Schematic of engineered dry swale (Claytor and Schueler 1996)

Applications and Restrictions

- Most applicable for roadside drainage channels, however people tend to park in them which kills the vegetation and causes erosion problems.

- Must be an accepted development alternative as set forth by local ordinances.

- Best suited to residential developments but may also be used for commercial and industrial sites.

Active Pollutant Removal Processes

Open vegetated channels provide increased surface area and extended contact time for pollutant interaction with soil and plant material. These two factors allow for enhanced pollutant removal via filtration, infiltration, microbial reactions, plant uptake and adsorption.

Estimated Percent Removal of a Dry Swale

| |

Water Quality Parameter

|

Removal Rate (%)

|

| |

Total Suspended Solids |

90

|

|

Total Phosphorus |

65

|

| |

Total Nitrogen |

50

|

| |

Nitrate |

80

|

| |

Metals |

80-90

|

(Claytor and Schueler 1996)

Construction

- The use of vegetated channels generally results in significant cost savings because it eliminates the need for traditional curb-and-gutter systems, thus reducing the required amount of concrete.

- Also, vegetated channels replace concrete and/or rip-rap drainage channels which are extremely expensive.

- As sized for a typical residential development, curb-and-gutter costs from $14 to $20 per linear foot, while vegetated channels cost between $7 and $10 per linear foot (Lovett 1999).

Maintenance

- Mow grassed areas.

- Inspect periodically and repair to correct for erosion and channel scour.

Environmental Benefits

- Recharge groundwater supplies.

- Enhance pollutant removal.

- Help to maintain predevelopment hydrograph for all design storms.

Additional Benefits

- Aesthetically more pleasing than curb-and-gutter systems.

- Consume very little buildable land.

- Preserve rural character.

Contacts and References

- Claytor, R.A. and T.R. Schueler. 1996. Design of Stormwater Filtering Systems. A report prepared for Chesapeake Research Consortium, Inc. December. Ellicott City, MD: Center for Watershed Protection.

- Note: See Sommerset (1-6) and Northridge (9-5) case studies for information on the use of dry grassed swales.

Streambank Restoration/Bioengineering

Bioengineering is a method of halting property loss caused by eroding streambanks. It is accomplished by regrading the bank and planting with species that are resistant to erosion. This method is much less expensive than structural methods, such as armoring a streambank with rip-rap, and is aesthetically much more pleasing.

Introduction

- Designed to produce a forested ecosystem along the stream that will function in the same manner and provide the same benefits as a natural streamside ecosystem.

- Three basic approaches:

- hard- structural (e.g. rip-rap, concrete channelization, straightening channels)

- soft-vegetative

- bioengineering: combination of hard and soft approaches (Firehock and Doherty 1995)

- This chapter will address bioengineering techniques.

Example drawing for a bioengineering project (Wiggins 1997; Thomas 1997)

Applications and Restrictions

- Each streambank restoration project is site specific and should be tailored to meet the needs of your specific stream and watershed.

- Factors that should be considered in a restoration project:

- designated and desired uses of the stream (e.g. drinking water, recreation)

- land uses in the watershed

- streambank stability

- susceptibility to erosion

- velocity and flow of the stream

Active Pollutant Removal Processes

Streambank restoration projects are designed to produce mature forested buffer zones. If successful, the restored buffer zone will use natural ecosystems to control stormwater quantity and quality. They provide increased surface area and extended contact time for pollutant interaction with soil and plant material. These two factors allow for enhanced pollutant removal via filtration, infiltration, microbial reactions, plant uptake and adsorption. They also reduce thermal pollution by shading the stream. The estimated pollutant removal rates of streambanks which are successfully restored to a forested condition and are of adequate width should be similar to that of riparian buffers. (See Chapter 8 on riparian buffers for pollutant removal percentages.)

Economic and Marketing Benefits

- Increased property values due to aesthetic improvements of the streambank.

- Creates an opportunity for community involvement and a greener image of the developer and the development.

- Reduces erosion and halts property loss.

Construction

- Costs vary widely depending on the type of stabilization performed. Generally structural approaches are the most expensive followed by bioengineering and vegetative practices, respectively.

- Concrete channelization projects are very expensive and can cost up to $100,000 per linear foot while vegetative methods cost approximately $100 per linear foot (Firehock and Doherty 1995).

Maintenance (Wiggins 1997)

- Inspect on a regular basis for at least a year following completion to check for dead plants that may require replacement, gully formation, excessive weed growth and insect infestation.

- Take before, during and after pictures to monitor changes in the stream and its surroundings.

Environmental Benefits

- Restores pre-development streambank conditions (i.e. forested environment).

- Enhances pollutant removal.

- Shades the stream to prevent thermal pollution (i.e. low oxygen levels) of the stream and its receiving waters.

Additional Benefits

- Provides food, cover and habitat for wildlife

Comments

Streambank restoration projects provide an excellent opportunity to involve the public in a project to improve the environment. Much of the labor required can be performed by volunteers, which will reduce costs and aid in the marketing of a development. With a little effort and creativity, a stream bank restoration project can be turned into a community project. A good marketing idea is to hold a public meeting or cookout where people can express their views, be educated on the value of the stream and socialize amongst themselves and the development community.

Contacts and References

- Hal Wiggins. Environmental Scientist, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Spotsylvania, VA. .

- Firehock, K. and J. Doherty. 1995. A Citizen's Streambank Restoration Handbook. Gaithersburg, MD: Save Our Streams Program, Izaak Walton League of America, Inc.

- Laurent, S., ed. 1992. Engineering Field Handbook-Chapter 18: Soil Bioengineering for Upland Slope Protection and Erosion Reduction. October. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service.

Streambank Restoration/Bioengineering

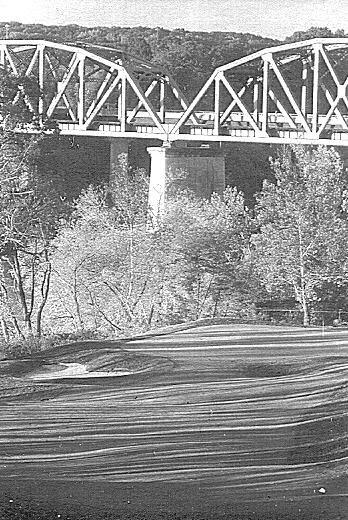

Massaponnax Creek at Lee's Hill

Severely eroded sections of Massaponnax Creek posed not only an environmental hazard but were also an eyesore to Lee's Hill and its golf course. The streambanks were revegetated and stabilized which enhanced the aesthetic appeal of the creek and saved the developer approximately $120,000 over what it would have cost to stabilize with rip-rap alone.

Had they done it with all rock [rip-rap], it would have been about three times as expensive.

- David Tice, Project Consultant, North American Resource Management Inc. (1997)

Introduction to Massaponnax Creek and Lee's Hill

- 1acre residential/golf course development near Southpoint in Spotsylvania County, VA.

- Massaponnax Creek, a tributary of Ruffin's Pond and the Rappahannock River, flows through the development and the golf course.

- As part of a mitigation plan prescribed by the Army Corps of Engineers, Lee's Hill Partnership was required to restore 1.28 acres of terrestrial streambank.

Feature BMP: Streambank Bioengineering (Tice 1997)

- Streambanks were first regraded (generally to a 3:1 slope) and class I rip-rap was placed at the toe of the slope to a 2-year storm depth.

- Live stakes, brush mattresses, fascines and brush layers were then used to stabilize eroded streambanks. The plantings were chosen to establish woody vegetation on the streambank.

- Some critical areas were covered to higher elevations with the rip-rap.

Economic and Marketing Benefits

- Realized cost savings of approximately $46,000.

Cost Comparison-Bioengineering vs. Rip-rap

| |

All rip-rap

|

Bioengineering and rip-rap

|

Cost Savings

|

| |

|

Rip-rap

|

Bioengineering

|

|

| Size (acres) |

1.28

|

.38

|

.90

|

|

| Cost per acre |

$82,900

|

$82,900

|

$31,700

|

|

| Cost for site |

$106,112

|

$31,502

|

$28,530

|

|

| Total Costs |

$106,112

|

$60,032

|

$46,080

|

Construction (Tice 1997)

- Total costs for the project were approximately $60,000, including labor, regrading of the streambank, bioengineering materials, rip-rap and consultant fees.

Maintenance

- Designed to not require any maintenance (Tice 1997). Nelson Cole, project manager for Lee's Hill Development Partnership, stated that the project has required no maintenance (1997).

- Required only when erosion occurs or vegetation dies.

Before After

Comments

David Tice states that additional cost savings could have been realized had less rip-rap been used on the project. The contractors and developers were overly cautious with the stone in some sections (i.e. used more stone than was required), and therefore made the project more expensive than necessary (1997).

Contacts and References

- David Hazel. Hazel Land Development Co., Inc. Fredericksburg, VA. .

- David A. Tice. David Tice and Associates, Ltd. Charlottesville, VA. .

- Hal Wiggins. Environmental Scientist, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Fredericksburg, VA. .

Streambank Restoration/Bioengineering

Massaponnax Creek at Southpoint

A severely eroding streambank was causing property valued at $10 per square foot to be lost to erosion (Elliot 1997). Through the use of bioengineering techniques, the erosion was halted, the aesthetics of the creek were improved and the developer realized a cost savings of at least $4,550 over the cost of doing the same project with rip-rap alone.

Doing it that way with natural vegetation was a huge cost savings and certainly aesthetically more pleasing.

- Jules Elliot, Developer and Property Owner, Elliot & Associates Inc. (1997)

Introduction to Massaponnax Creek and Southpoint

- Massaponnax Creek is a tributary of the Rappahannock River which flows through Spotsylvania County and into Ruffin's Pond before joining the Rappahannock River.

- At Southpoint the creek flows through the Massaponnax Commercial Development at the junction of Rt. 1 and Interstate 95.

- The restoration area is 300 feet long and was graded to a width of 20 feet.

Feature BMP: Streambank Bioengineering (Thomas 1997)

- Streambanks were regraded to a 3:1 slope and class I rip-rap was placed at the toe to a width of 4 feet up the streambank (2-year storm depth).

- The graded streambank was dragged with a chain link fence apparatus, planted with a Critical Area Planting Mix from the VA Department of Forestry and covered with straw. Dogwoods and other woody species were also planted.

Economic and Marketing Benefits

- Realized significant cost savings of $4,550. The alternative to bioengineering would have been to armor the bank with rip-rap to a height of 10 feet or more at a cost of $35.00 per square yard for rip-rap (Thomas 1997).

- Translates to $23.10 per linear foot for bioengineering compared to $38.33 per linear foot for rip-rap, a savings of over $15.00 per linear foot

Cost Comparison-Bioengineering vs. Rip-rap

| |

All rip-rap

|

Bioengineering and rip-rap

|

Cost Savings

|

| Rip-rap |

$11,500

|

$4,550

|

$6,950

|

| Planting |

$0

|

$2,400

|

-$2,440

|

| Grading |

same

|

same

|

$0

|

| Total Costs |

$11,500

|

$6,950

|

$4,550

|

Before After (1 year later)

(Wiggins 1997)

Construction (Thomas 1997)

- Total construction costs excluding grading was $6,950. Grading costs are not a factor, because they will be the same regardless if bioengineering or rip-rap is used.

Maintenance

- Required only when erosion occurs. No erosion problems have been observed at this particular site, and therefore no maintenance has been performed (Wiggins 1997).

- The developer has reported no problems of any kind with the restoration site and says that it has required no maintenance (Elliot 1997).

Comments

The Army Corps of Engineers emphasizes that the permitting process for bioengineering is just as easy or easier than that for traditional techniques such as rip-rap stabilization. The Corps is frequently approached by developers and contractors with plans for structural stabilization, however, they often convince them to use bioengineering, because it is so much cheaper.

Contacts and References

- Jules Elliot. Developer, Elliot & Associates Inc. Fredericksburg, VA. .

- Rick Thomas. J.K. Timmons & Associates, P.C. Richmond, VA. .

- Hal Wiggins. Environmental Scientist, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Fredericksburg, VA. .

Streamside Buffers